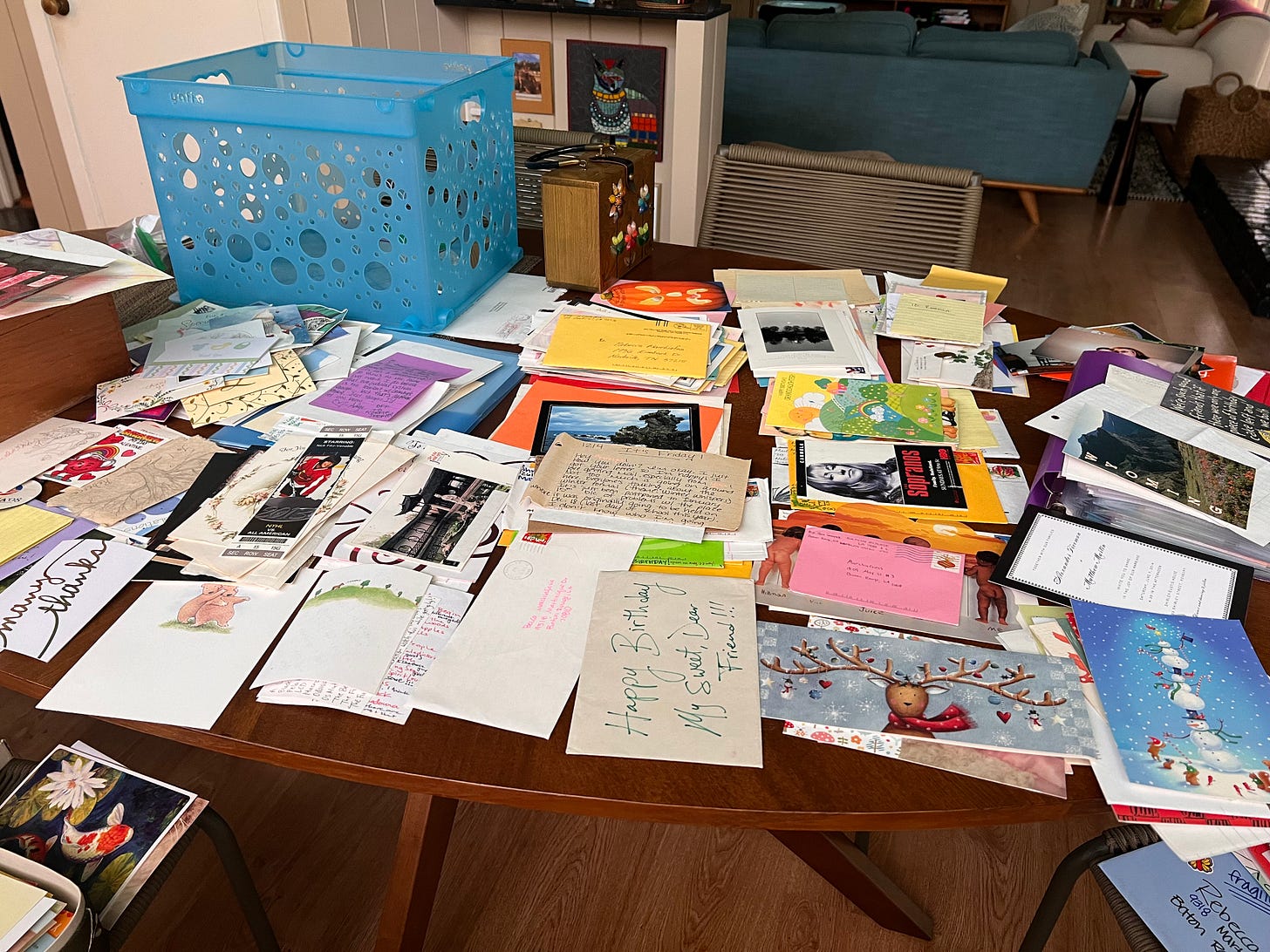

In July, work was slow as it often is in the summer, so I embarked on an organizing project. I pulled out various boxes that collectively contained 40 years worth of cards, notes and letters, and went to work to organize them.

I didn’t read everything—that would’ve taken more time than I had—but going through these things was a trip. From notes between childhood friends to bad high school poetry to letters from relatives who have passed away, there were moments of laughter, sadness and poignancy.

And amidst it all, I came across a copy of a letter I wrote to the CEO of a company I used to work for.

When I wrote this letter, I was leaving my job to pursue my next opportunity, so I took the chance to thank the CEO for the experience and for all I had learned working for his company. And being who I am, I also shared about my employee experience and offered some recommendations.

How presumptuous of me, right? I was a young professional addressing an older, seasoned CEO. Still, I calculated that I was leaving the company. What did I have to lose?

In the letter, I describe experience with toxic conflict in the workplace and urge investment in repairing workplace relationships. I explain how communication breakdowns due to toxic conflict got in the way of doing the work. I address unhelpful narratives that I’d heard to dismiss and explain away the conflict issues in the organization.

To some, this might seem weird. To me, it was an act of care. I cared about the company and those who worked in it, and wanted to offer up my observations and suggestions in case they could be helpful.

I doubt anything came from it, but re-reading the letter so many years later, I was amazed. Don’t get me wrong, there are plenty of things from my younger life that I now find embarrassing, but in this case? I was proud of twenty-something me.

Coming across the letter was a reminder of experiences in the workplace that I had long forgotten and it illuminated even more why I now do the work that I do. These days when I talk about conflict at work, I mostly talk about my experiences managing conflict as a leader and people manager. Those are my most recent experiences and memories. In this case, though, I was a lower-level employee caught in an unhealthy environment that people with more power and authority were not addressing.

Revisiting the letter, I could see a direct line between that experience and my founding of Culture Work.

Making Time for Conflict = Making Time for People

When people ask me about red flags of toxic workplaces, one that I warn about is the absence of conflict or disagreement. This may seem counterintuitive: don’t we want everyone to get along?

In actuality, some amount of conflict is part of a healthy environment. Too much conflict or poorly-handled conflict, as I’ve experienced, is not good. And yet the total absence of conflict is also a problem.

In healthy environments, people work and collaborate well together. Part of collaborating well is surfacing and working through conflict effectively.

If people in a workplace always agree or go along with what other people say, it tells me that they don’t feel safe to disagree or speak up about problems, which is a risk factor for harassment, discrimination and a toxic work environment.

Learning to effectively navigate conflict is essential to building healthy relationships and healthy environments. When we make time for conflict and build our capacity for handling it, we show that we value people and relationships in the workplace.

The Time Conundrum

Making time to address conflict is easier said than done. I commonly hear from leaders and managers that they don’t have time or capacity to deal with conflict when it arises, and that employees should be able to resolve issues on their own. I absolutely get it: as a leader, manager, and introvert, I have felt the exact same way—even with my conflict beliefs.

I would counter, though, that we don’t have time to avoid conflict—for a number of reasons:

Avoiding conflict often takes more time and energy in the long run.

Avoidance of conflict usually doesn’t resolve anything. What usually happens with avoidance is that conflict, resentment and breakdowns in communication build up until there’s no way to avoid it any longer. And by then, it can be a lot more difficult to resolve conflicts and rebuild trust.

Avoiding conflict damages relationships.

When we’re talking about conflict, we’re talking about people and relationships. By avoiding conflict, we’re avoiding conversations about people’s experiences, values and needs. We’re demonstrating that our workplace relationships are not important. Ultimately, this can damage relationships, trust, and collaborations in ways that harm employees and the organization overall.

Avoiding conflict sets a bad example.

As leaders and managers, the behaviors we engage in aren’t just about us. They influence the work environment in our team and organization as a whole. Do we want team members to be able to address and work through issues with one another without even coming to us? Do we want to resolve issues before they escalate into bigger problems? If so, it’s key to model effective ways of handling conflict and to intentionally define an organization’s conflict culture to shape employee approaches to this normal part of work.

When it comes to conflict, the cost of inaction can be high.

Fear of Conflict

Now, let’s get real. Often, underneath the thought, “I don’t have time to deal with this,” there are other thoughts:

“Trying to fix this will make it worse.”

“I don’t know how to handle this.”

“Nothing can be done about this.”

Time is a real issue, but a common underlying problem can be fear of making things worse and of not having the confidence to handle conflict effectively. So, we avoid it and hope for the best. We delegate resolution to the employees in conflict regardless of whether they have the tools or resources to resolve the issue.

The thing is, the answer to fear of conflict is not avoidance. The answer to fear of conflict is building capacity. Defining our organization’s conflict culture, building internal knowledge and skills around handling conflict, and connecting to external resources for support are all ways we can build capacity to effectively handle conflict at work.

And it must be acknowledged that unhealthy approaches to conflict can lead to breakdowns and even estrangement in relationships. These unhealthy approaches can include:

Denial, avoidance or suppression of conflict

Behaviors where a person seeks to dominate and “win” the argument, or goes into a conversation only wanting to get their way

Dismissing or minimizing concerns

Personal attacks

Wanting to be heard without listening

While unhealthy approaches to conflict can be destructive, healthier approaches can lead to creative and generative forms of conflict. They can lead to good things. They can strengthen relationships. How we handle conflict makes a difference.

Conflict is an Opportunity

Dealing with conflict effectively in relationships means both or all people involved have the tools to do so, and this isn’t a given. This is why facilitators and mediators can be useful: they provide support for people to have difficult conversations and identify solutions to problems that people may not be able to do on their own.

Yet, as a facilitator, I don’t control the outcomes of conflict resolution conversations. I show up and do my best, but that won’t be enough if participants in the conversation aren’t willing to do their part.

Fortunately, I’ve facilitated enough conversations to commonly hear people express that they feel relieved and more hopeful at the end of it. This is validating when people often come to such conversations feeling anxious, skeptical and relatively hopeless that things can get better. And that really gets to the heart of conflict work: in many ways, it is the work of generating hope.

In any group of people, conflict is inevitable, whether it's hidden or visible. Once we recognize that conflict is normal in relationships and workplaces, we have a choice. We can give in to fear and avoidance, or we can work to build capacity to approach conflict differently: with intention, curiosity and supportive resources. Challenging ourselves and our organizations to view conflict as an opportunity—to get curious, ask questions, learn, and grow—is a key culture shift that can catalyze positive change.

The question for organizations and their leaders is not, “Do we have conflict?” The question is, “How do we view and handle conflict?” Asking and answering this question is essential to building a healthy workplace.

I support organizations and teams in handling conflict, improving communication and collaboration, and building intentional conflict cultures. Visit my website or schedule a free consultation to learn more.