Titanic Takeaways

Leadership Lessons from a Century-Old Disaster

Earlier this year, I rewatched the 1997 film Titanic.

I was fourteen years old when it came out and saw it no less than four times in the theater (elite numbers).

As a teen, I was more into a certain actor and the drama of the story.

These days, my favorite part is when—spoiler alert—Jack is freezing to death in the frigid waters of the North Atlantic, and he says to Rose: “I plan to write a strongly worded letter to the White Star Line about this.”

Forget Charlotte, forget Miranda: I’m definitely a Jack. You can bet I’d say something similar were I in his situation.

And while it’s a funny line, it also cuts to the core of the whole tragedy.

The Titanic disaster is often portrayed as being caused by the hubris of men who designed and owned the ship, and who wanted to prove how swift, powerful, and—ironically—unsinkable it was.

This was a big part of the story, and there’s more to it.

The sinking of the Titanic is a story of hubris. It is also a story of institutional neglect and the limitations of compliance.

Inspired by my recent rewatch, here are a few takeaways for leaders from the sinking of the Titanic.

Compliance is the floor, not the ceiling.

This common saying reminds us that, while compliance is necessary to organizations, it is not always sufficient for mitigating risk.

Consider that the Titanic was in full compliance with all maritime laws and regulations of its day. In fact, despite not having nearly enough lifeboats for those on board, it had more lifeboats than were required by law.

It wasn’t enough to avoid a shocking, massive disaster that still reverberates in our culture over 100 years later.

Traditional approaches to compliance often focus on outputs, asking: “What laws are we required to follow? What reports do we have to submit? What boxes do we have to check?”

A more intentional culture invites a focus on outcomes, asking: “What results do we want to create? How can we get to these results?”

“What would it take to protect all of our passengers and crew if a disaster occurs at sea?” If the White Star Line had asked this question, they could have defined that as a goal and taken the necessary steps to achieve it.

When it comes to protecting our organizations, staff safety, and client or customer well-being, compliance is the floor—not the ceiling.

Safety matters across the board.

68% of the people on board the Titanic perished in its sinking, a shocking statistic.

This was not due to an iceberg. It was due to inadequate systems and resources for saving the lives of those on board.

And while we often think of the passengers who lost their lives, an estimated 685 crew members were among those who died. These were employees of the White Star Line who were not protected by their employer.

Consider also that 39% of first class passengers died, whereas 76% of third class passengers died. It’s not news that the lives of first-class passengers were valued more than those of lower classes, but it’s important to remember that this isn’t an inevitability: it’s the result of choices informed by values.

In a workplace, are there disparities in outcomes related to safety and well-being? Does an organization value the lives or well-being of some more than others? Or is it committed to protecting everyone’s safety at work, regardless of their demographics or position?

Part of workplace culture is how we affirm, in policy and practice, that everyone’s safety and well-being matters.

Accepting inconvenient data is part of leadership.

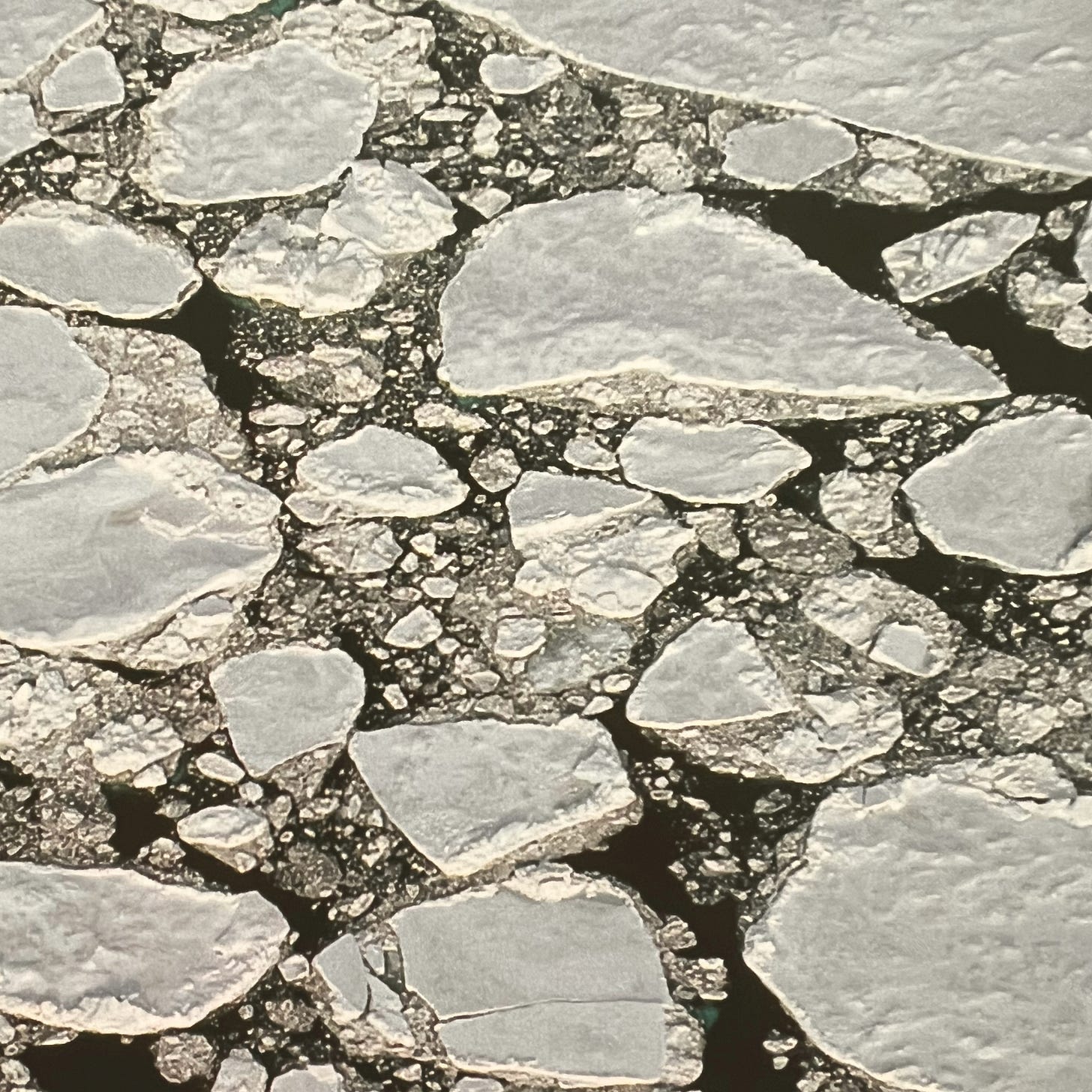

The Titanic received several ice warnings leading up to its collision with the infamous iceberg. In response, the captain ordered the ship further south, but did not reduce its speed. This fateful decision represents the choice to value speed over people’s lives.

The ice fields were not a desired reality, but they did, in fact, exist.

When faced with inconvenient data, are organizational leaders responsive and willing to be flexible based on what is learned? Are they committed to valuing people’s lives and well-being over arbitrary goals? Or do they remain committed to delusion and foolhardy, high-risk approaches?

How a workplace responds to inconvenient data is part of its culture.

Priorities matter.

The Titanic’s wireless operator received ice warnings that he passed on to the appropriate parties and others that he didn’t pass on. The night of the sinking, a nearby ship radioed the Titanic to say they were stopped and surrounded by ice.

The Titanic’s operator responded: “Shut up! I am busy.” Reportedly, he set this message aside with the intention of passing it along once he finished communicating a backlog of personal messages from passengers.

Within the hour, the Titanic collided with an iceberg, and the rest is history.

I don’t bring this up to condemn this crew member. Hindsight is 20/20, as they say, and he perished in the sinking at only 25 years old. He was busy with a backlog of passenger messages after the radio equipment had previously malfunctioned.

It’s possible that he saw higher-ups not taking previous ice warnings seriously and learned from the example they set that these warnings were a distraction.

Yet again, this story shows the importance of building a clear culture where safety is the top priority and everyone understands that—even if other things have to take a backseat.

Learning from mistakes is essential to building (and rebuilding) trust.

The Titanic disaster outraged the American public and led to legal changes in both American and international maritime laws:

In 1912, a subcommittee of the United States Senate Commerce Committee began conducting hearings on the event, leading to over 1,100 pages of transcripts that feature testimonies on passenger treatment, distress signals, and the inadequate supply of lifeboats and ignored ice warnings.

The committee produced a final report…ultimately concluded that “this incident clearly indicates the necessity of additional legislation to secure the safety of life at sea,” and provided a list of safety and legal recommendations.

The reaction wasn’t one of thoughts and prayers without action, nor was there a rush to judgment about what had transpired. A horrific event occurred and the government conducted an in-depth review to inform policy change that was then enacted to prevent similar disasters and better ensure safety in the future.

It may seem quaint by today’s standards, but organizations have an opportunity to set their own example in this area. Every workplace has an opportunity to determine how it responds when mistakes are made. How we as leaders respond to our own mini-disasters is a demonstration of our organization’s culture.

A complex set of events led to the sinking of the Titanic. Ultimately, the lives of the estimated 1,517 people who perished in the sinking could have been saved had the White Star Line done its due diligence to not only comply with laws, but to operate in reality-based ways and prioritize its passengers’ and workers’ lives.

The true disaster of this event was not that the ship sank, it’s that the White Star Line failed to ensure adequate systems and resources to save the lives of those on board in the event of a sinking.

Despite this disaster occurring over a century ago, the lessons offered by the Titanic’s legacy continue to reverberate. Will we listen? Will we learn?

Sources & Additional Reading:

The Titanic: A Case Study in Flawed Risk Management

The Titanic and the Law: Safety and Science

Timeline of the Titanic’s Final Hours | Events, Sinking, & Facts

After a busy spring and summer, I’ve been deep in reflection and planning mode.

You can visit a refreshed Culture Work website here with updated services.

Interested in services or a workshop for your team? Let’s connect!