CW: This essay discusses various disasters including Hurricanes Katrina, Gustav, Helene, and Louisiana’s 2016 floods.

Growing up in South Louisiana, I studied French from elementary school until 9th grade, when I completed my high school language requirements. I can’t converse much, but I can recite the alphabet and count in French as if it’s second nature, a holdover from this childhood education.

After studying French, I took three years of Latin until I graduated from high school. Latin taught me about the etymology of words and the connections between Romance languages. I loved learning about the history and meanings of words we use every day, but don’t think about much.

In college, I minored in Italian. My mother urged me to study Spanish because it was more relevant in the U.S., and while that was practical advice, I was influenced by my Italian heritage and an interest in Italian culture to learn the latter. Along with my planned minor, I had a goal of studying abroad in Italy and becoming a fluent speaker.

I did everything I set out to do: the minor, the study abroad, and I became conversationally fluent in Italian by the end of my year there. My crowning achievement was when the owner of a pensione in Venice mistook me for being a native Italian and was shocked to hear me speak effortless English with other travelers in the dining room. Of course, this was immediately followed by a trip to Sardinia where I could hardly understand any of the local dialect–a humbling experience that reminded me there’s always more to learn.

This was twenty years ago and I haven’t had the chance to return to Italy since, thanks to work obligations and financial limitations. Sadly, I’ve lost a lot of my Italian skills over time, but my interest in languages and etymology continues.

This is why I often present definitions of words to introduce essays on this blog. I think language matters and it’s important to have shared definitions when discussing a given topic. I remain curious about where our words come from and how their original and evolving meanings connect to culture.

_______

After three months of writing about the topic of conflict, I’d planned to lighten things up in October. Then, at the end of September, Hurricane Helene carved a path of destruction 800 miles long, devastating inland, mountainous areas in Western North Carolina and Eastern Tennessee in ways never before seen or experienced in our documented history.

While it didn’t impact my home, it felt close to home. I couldn’t stop thinking about natural disasters.

A year after returning home from Italy, I was in my last semester of college at LSU when Hurricane Katrina hit Louisiana in 2005 and devastated New Orleans and surrounding areas, altering our region forever. There is pre-Katrina and post-Katrina time, and 19 years on it remains a stark turning point.

After Katrina, my university canceled classes for a week and set up a shelter and field hospital. One night, my friends and I volunteered there from midnight to 6:00 a.m. and got breakfast at a local diner near campus afterward. Students from New Orleans universities joined our classes for the semester. At commencement, we would move our tassels before grades were finalized due to the disruption Katrina wrought. The diploma covers handed to us were empty inside.

Over the past few weeks, watching another region experience death, destruction and disruption on a similar scale to Katrina–with its own unique horrors and challenges–has been gut wrenching. The unprecedented nature of the situation has inevitably brought up memories of past disasters, not as isolated events but as a collective and escalating experience.

_______

People often think that on the Gulf Coast, we’re used to hurricanes. This is partly true. Hurricanes, including powerfully destructive ones, have always been a fact of life in this coastal region. Still, things have changed over the past two decades.

When I was young, people evacuated from New Orleans to Baton Rouge across 70 miles from vulnerability to relative safety. Then, in 2008, Hurricane Gustav shattered our sense of security in Baton Rouge, toppling oak trees all over the city, killing an elderly couple that had evacuated from their home closer to the coast, and leaving 85% of the city without power, in many cases for weeks. All told, 153 people died as a result of Gustav in the Caribbean and the U.S.

Then, in 2016, South Louisiana was devastated by unexpected, historic floods from a storm that had no name. Some of my colleagues’ homes were among the 146,000 that flooded. Our sexual violence crisis response efforts expanded, for a time, to include disaster response.

I’m a planner and a preventionist; I’m not made for crisis and chaos like some people are. Yet, living where I do and having done sexual assault response work has taught me ways to show up in crisis, trauma and disaster—from formal volunteering to donating to disaster relief efforts, and from holding space to helping clear out flooded homes and doing others’ laundry. There are countless big and small ways to help and support others after disaster strikes and I’ve seen firsthand how communities come together to make it through devastating situations.

_______

In 2021, I evacuated for the first time in my life from Hurricane Ida, driving all night with my partner and our cat to a friend’s place in Houston, spending over 10 hours in the car in stop-and-go traffic. After we arrived, I wrote on Instagram: “Our first time evacuating. Being from BR, you don’t evacuate. People evacuate to you. It took challenging my identity to convince me to leave.”

Hurricane Ida was the second-most destructive hurricane to ever hit Louisiana, behind Hurricane Katrina. Despite evacuating, I spent the night worried about and texting with loved ones back home.

When I decided to settle in Baton Rouge rather than New Orleans as an adult, it was largely because I’d grown up watching people evacuate from New Orleans as hurricanes approached. Baton Rouge felt safer and, honestly, easier in that regard, though that illusion has since been shattered.

And now, we’re seeing how climate change is not just a problem for those of us in coastal regions. We are living through what has been predicted for decades: rising temperatures leading to stronger, wetter and more rapidly intensifying storms. This expands the zone of impact and can give people less time to prepare and evacuate—and fewer places to evacuate to. The time between disasters is shortening, too, straining disaster relief resources and limiting time for healing and recovery.

As I write this essay, Hurricane Milton escalates from a Category 1 to a strong Category 5 hurricane in less than a day. I feel anxious despite it not being headed my way. I call my mother and we talk about why we’re both anxious about it: our family connections to Florida, our general empathy for people in harm’s way, our own trauma from past storms and concern for the future.

While Milton doesn’t end up being the “worst-case scenario,” it causes great destruction. I think back to Gustav, when the national media left because it wasn’t another Katrina and we were there to pick up the pieces: replacing blown-out windows and helping people whose homes had taken direct hits from gigantic oaks.

_______

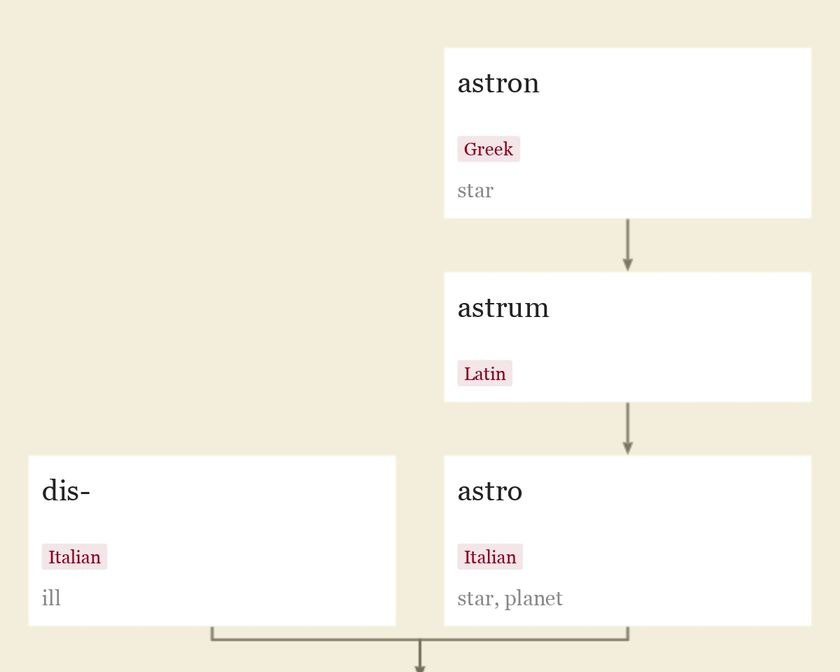

All of this witnessing and reflecting on disasters inevitably led me to ask: where does the word “disaster” come from? What does it mean in an etymological sense? A quick internet search taught me that its original meaning is “ill-starred.” I found this striking, as it evoked the idea of disasters being fated and unavoidable—of destruction written in the stars.

We often think of natural disasters as acts of God or nature—as things outside of our control. Yet, there are countless ways that humans and institutions shape the outcome of disasters.

When I first began learning about the concept of institutional betrayal, I attended a virtual talk by Dr. Jennifer Freyd in which she spoke about Hurricane Katrina as having elements of both a natural disaster and a man-made disaster due to institutional failures.

As a Louisianan, this was old news to me. Hurricane Katrina had tracked more eastward than expected at the eleventh hour, sparing New Orleans a direct hit. It was institutional failures that led to levees failing and a devastatingly poor disaster response, which led to greater destruction, a higher death toll, and far more trauma than was inevitable.

What I learned from Dr. Freyd’s presentation was that these institutional failures meant that Hurricane Katrina scores high on a betrayal scale, which compounds trauma as compared to natural disasters where institutions effectively prevent and respond to harm. In these institutional approaches toward disaster prevention, mitigation, and recovery, there is a great deal of power to affect the outcomes of natural disasters.

Beyond our major societal institutions, each of our organizations is an institution that has the capacity to influence disaster outcomes and other effects of climate change, which are workplace health and safety issues.

Extreme weather events and wildfires threaten life and property, making it crucial for workplaces to develop emergency plans. Along with storms, flooding, and wildfire risks, extreme temperatures create greater heat-related risks, making it incumbent upon workplaces to protect employees from heat-related illness and death.

As I scrolled through TikTok videos of the devastation wrought by Hurricane Helene, I came across a story of a plastics factory whose employees were required to report to work the day of the storm. Eleven employees were swept away in floodwaters. Some were rescued, but recent reports show that five of these employees died and one is still missing.

The company denies any wrongdoing and disputes the accounts of surviving employees, but the outcome is that employee safety was not ensured. That matters. Company representatives claim no one was told they would be fired if they left work. Yet, if employees were told to report to work, the threat of termination is implicit, leaving people to balance the risk of losing their lives or their livelihoods: a terrible position to be put in.

This example makes it clear how important it is to take severe weather seriously especially in an era of climate change, to err on the side of caution, and to communicate clearly and directly with employees so that there is no question about employee safety being the top priority.

Anything else is an institutional failure. Lives were lost that could possibly have been saved had institutional leaders done things differently. This is more than a tragedy: it is a deep betrayal.

As we collectively navigate this new and evolving normal, emergency planning and disaster response is a responsibility of all organizational leaders. And even in the absence of a plan, employee health and safety should be paramount. While some aspects of disasters may be written in the stars, we can use our courage, humanity and power as leaders to make a difference in the outcomes.

Disaster Planning Resources for Organizations

Nonprofit Emergency Plans: What You Need to Know

The Disaster Management Cycle: 5 Key Stages & How Leaders Can Help Prepare

Resources for Disaster and Emergency Planning - Nonprofit Center of Northeast Florida

The road to recovery from Helene will be long and all affected are in my thoughts. I welcome knowledgeable readers to drop disaster relief donation recommendations into the comments.

In what’s becoming an October tradition, I’m re-sharing an essay I originally published in October 2022, “The Horrors of Work Email Ghosting.” Consider it a little lagniappe.

Very interesting piece. With my clients, the topic of stress as an underlying factor comes up a lot. People usually think of stress as purely mental - hence the phrase, "I don't feel stressed" comes up a lot in my conversations. But my assessments point to undue burden in the body on physiologic level - through diet and external impacts of trauma that just take root in the body and resist letting go. Adding the more recent complications of work expectations and environmental disasters is, indeed, traumatic and concerning.